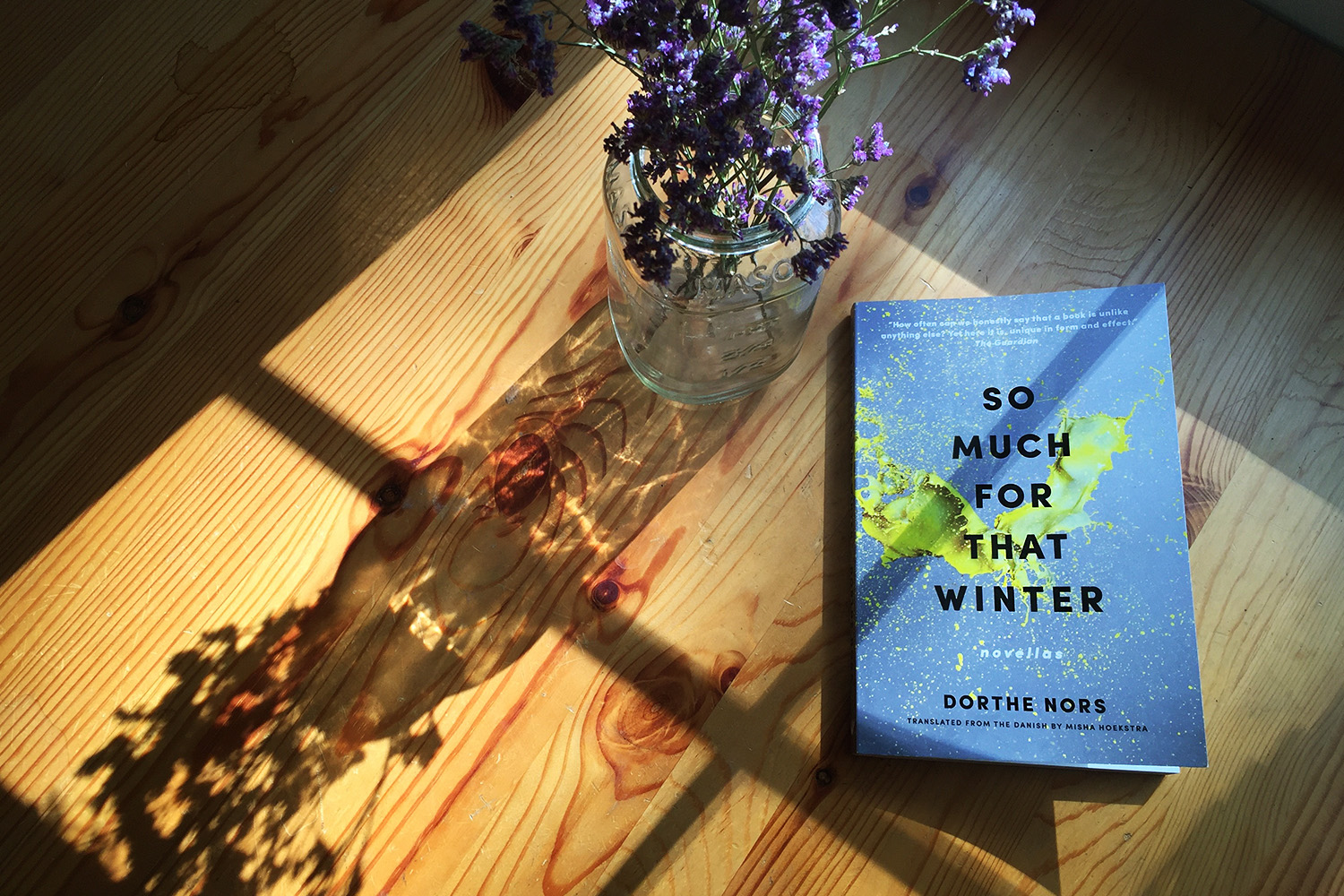

So Much for That Winter (Graywolf Press, 2016) includes two novellas by Danish author Dorthe Nors, “Minna Needs Rehearsal Space” and “Days.”

“Minna Needs Rehearsal Space” is told in single sentences, one stacked neatly on top of the next. Such a format may appear to be restrictive, too rigid for storytelling, but in fact it reads as smoothly as the one-liners we scroll through every day; the headlines and status updates kindly packaged and delivered to our screens by the likes of Facebook and Twitter. Our thoughts, even our ideas, are inevitably shaped and molded by the platforms through which they are expressed. Therefore, we subject our thoughts to rules of expression that are increasingly governed by private media corporations. Let us hope that we are in good hands. “Minna Needs Rehearsal Space” rings familiar because we have been primed to consume text in this very way. Meet our protagonist’s ex-boyfriend, Lars, for example:

“Lars is a network person.”

“Lars makes the pigeons rise.”

“Lars has deadlines.”

“Lars introduced himself with his full name.”

These are declarations rather than subtleties, loosely connected though just enough. It is slightly unsettling that a few brief sentences allow us to become familiar with a person, or at least familiar enough to pass judgment, which we do. Perhaps we all run the risk of being summarized in a few sentences, as if none of us are as complicated as we like to imagine. But I think we are. And I think we run the risk of growing impatient of details and explanations, of reading anything of length, or of politely sitting through a friend’s long-winded story. Currently, we may prefer what is brief and to-the-point, but soon we may require it.

Of course, to assume that short declarations are inherently lacking in substance and meaning is entirely misguided. There is poetry, after all. Why use more words than necessary if one has the skill to pluck only those that are essential, to lay them out, arrange and serve to make the sharpest point. This is how we meet our protagonist’s nemesis, Linda Lund, whose assaults are as cruel as they are straightforward:

“Linda pulled out a mental machete.”

“Linda slashed a couple times.”

“Linda said, That dress will blend into the curtain.”

“Linda said, What’s your name again?”

“Minna almost couldn’t perform afterward.”

The story’s format also reveals how a single thought leads to the next, methodically and almost comically, as our minds continuously string together kernels of information:

“Minna’s gone for a walk in town.”

“Svaneke’s lovely.”

“Svaneke’s light yellow.”

“Svaneke’s a set piece, thinks Minna.”

The second story, “Days,” dives even deeper into a woman’s thought process as she chronicles her day-to-day in a series of lists. The trivial and the sacred sit side-by-side, so that in one moment she is thinking about the dentist while boiling eggs, and in the next:

“7. wrote a crucial note,”

“8. had an attack of vulnerability from the silence that fights back.”

I select every book I read as if it were some kind of momentous commitment, like I am in it for the long haul, so it is always a surprise when a book slips in to make its mark so quickly. If forevermore we are obliged to think in headlines and status updates, let us sound like Dorthe Nors.

*

*

“Minna Needs Rehearsal Space” from So Much for That Winter

By Dorthe Nors

Published 2016 by Graywolf Press