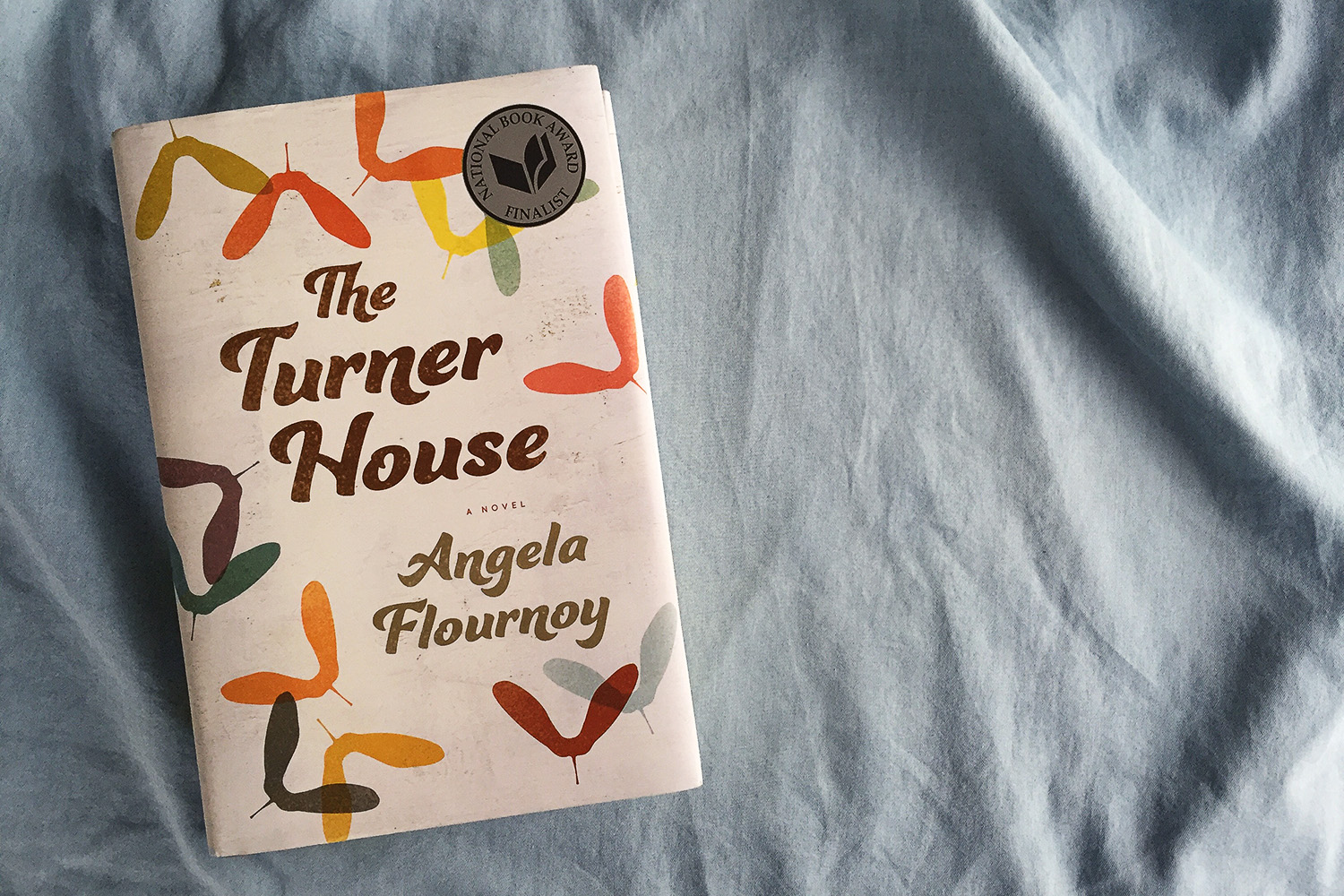

I promised myself to catch up on the books that I missed in 2015, in whatever meager way that I could, and I’m using the first few weeks of the new year to do just that. 2016, please be patient. I have five books on my catch up list, and I recently finished the first, The Turner House by Angela Flournoy. The book was a finalist for the 2015 National Book Award for Fiction, an impressive feat for a first-time author. My reading of The Turner House spanned countless locations, including the messy floor of an old apartment, the empty floor of a new home, on a plane flying south, under a weak light bulb in the early morning dark, and at Triste Cafe while drinking a $4 glass of red wine, where I was delighted to find the woman to my left engaged in similar activities (different book, same wine).

The Turner House is the story of Francis and Viola Turner and their 13 children, and continuously jumps between two eras. The first era stretches from 1944 to 1951, during which we learn of Francis and Viola’s Arkansas beginnings and their move to Detroit. The second era takes place in Spring 2008 and focuses on the children. While the eldest, Cha-Cha, is a baby in some pages of the book, in others he is 64 years old; the book stretches far and wide, in the way good ones do. At the center of the story is the house they grew up in, which now sits in a nearly abandoned East Side Detroit neighborhood. Francis is long dead and Viola is ill, so the children must debate what to do with the house. The book is described as “a major contribution to the literature on American families,” and it is a largely unromantic one, as in full of health problems and resentment and awkward moments and lost jobs. The book does not relieve readers of reality’s blemishes, but rather scatters them throughout its pages, creating a world that is recognizable, and thus meaningful beyond the dealings of one particular family.

The Turner House reminds me of the legacies that are behind each of us, of the infinitely nuanced lives that precede our own, yet how so much of it remains unknown; either forgotten or erroneously retold or simply never shared, sometimes with intention. I think of my own day-to-day, stories woven together from this and that, and I wonder if any of it will live on, how quickly details can lose their precision. And perhaps that is perfectly alright. But if that doesn’t sit well with you, The Turner House offers hope, as it suggests that in a myriad of ways, for better or for worse, the past is inherited by all of us, and even the details seem to work themselves in.

The Turner House is the story of Francis and Viola Turner and their 13 children, and continuously jumps between two eras. The first era stretches from 1944 to 1951, during which we learn of Francis and Viola’s Arkansas beginnings and their move to Detroit. The second era takes place in Spring 2008 and focuses on the children. While the eldest, Cha-Cha, is a baby in some pages of the book, in others he is 64 years old; the book stretches far and wide, in the way good ones do. At the center of the story is the house they grew up in, which now sits in a nearly abandoned East Side Detroit neighborhood. Francis is long dead and Viola is ill, so the children must debate what to do with the house. The book is described as “a major contribution to the literature on American families,” and it is a largely unromantic one, as in full of health problems and resentment and awkward moments and lost jobs. The book does not relieve readers of reality’s blemishes, but rather scatters them throughout its pages, creating a world that is recognizable, and thus meaningful beyond the dealings of one particular family.

The Turner House reminds me of the legacies that are behind each of us, of the infinitely nuanced lives that precede our own, yet how so much of it remains unknown; either forgotten or erroneously retold or simply never shared, sometimes with intention. I think of my own day-to-day, stories woven together from this and that, and I wonder if any of it will live on, how quickly details can lose their precision. And perhaps that is perfectly alright. But if that doesn’t sit well with you, The Turner House offers hope, as it suggests that in a myriad of ways, for better or for worse, the past is inherited by all of us, and even the details seem to work themselves in.

Post-Reading

Post-Reading