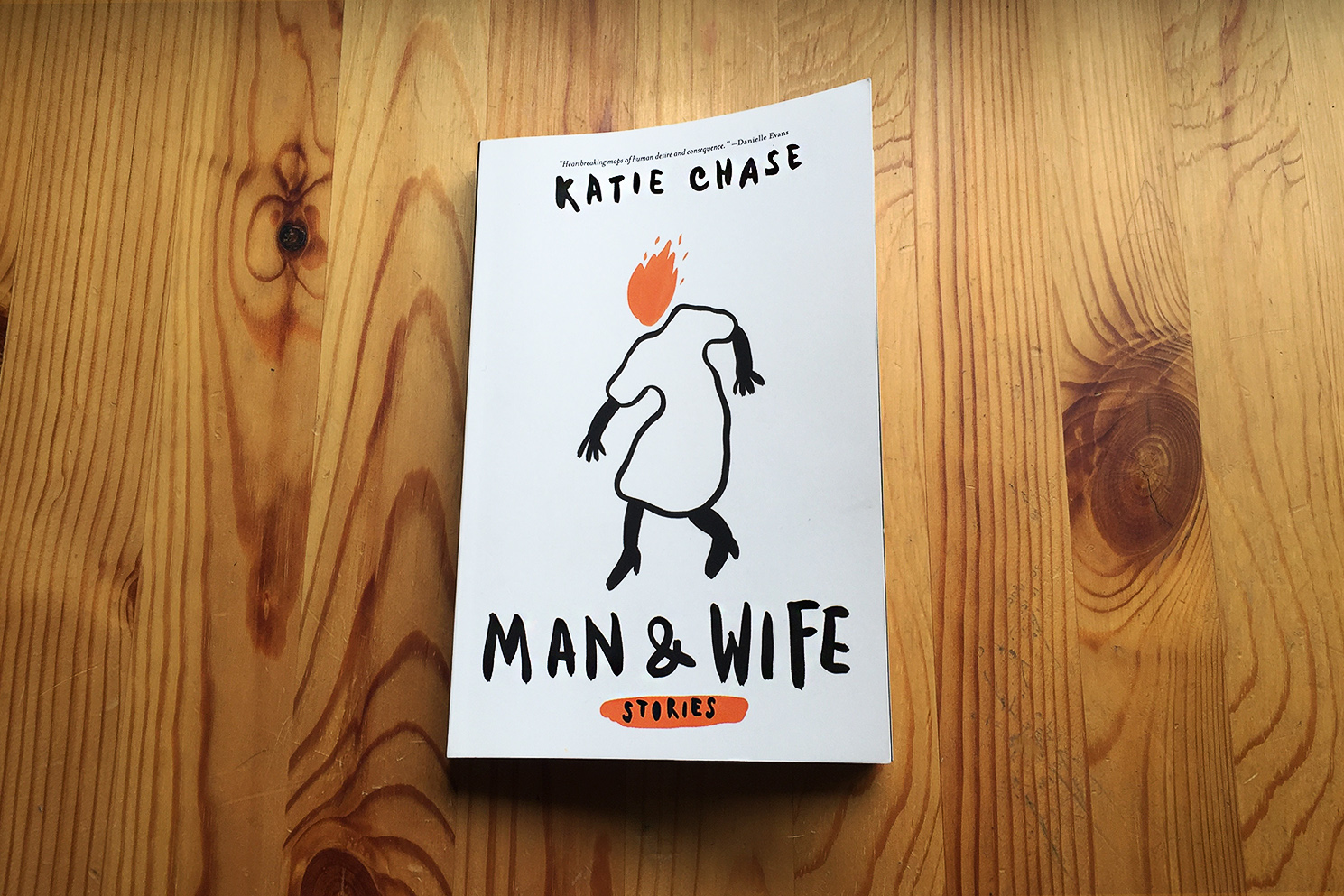

There is no skimming with short stories, especially when they are so good they test you as a reader, forcing you to take a piece of information——maybe a single sentence or even a single word——and to remember it, to carry it with you until it makes sense and becomes useful. Each of the eight short stories in Katie Chase’s Man and Wife (A Strange Object, 2016) carries a palpable sense that all is not quite right in the world, as if the seams of normalcy threaten to burst, which they do. In each story you suspect that there are clues hidden just below the surface, and that if you read closely enough, you would crack the code.

“Man and Wife” was included in the 2008 edition of The Best American Short Stories before debuting as the center piece of this collection of the same name. The parents of young Mary Ellen arrange for her to marry Mr. Morrison, contract and all, because “promising” a daughter to marry a much older man is normal, done with love and care. The story hovers between what is normal and perverse, until you wonder whether there is something just as perverse about those very things we consider normal; like how marriage is nothing short of a signed legal document; or how we obsess over weddings; or how “men talk business” while women bustle through domestic chores. You realize that what is portrayed as perverse——a young girl being groomed and trained for an arranged marriage——is simply an exaggeration. Women are in fact encouraged to serve and to please, and for Mary Ellen, this means to cook, sew, polish silver and remain silent unless spoken to. I first heard this idea articulated by the wonderful Eve Ensler, who says this in her TED talk:

“I’ve been talking to girls for five years, and one of the things that I’ve seen is true everywhere is that the verb that’s been enforced on girl is the verb “to please.” Girls are trained to please.”

None of the characters react to the perverse because it has been normalized, just like in our own lives. This suggests that others’ behavior and attitudes, those of the group, should never serve as the litmus test for what is right, normal or good. As readers, we prove how quickly questionable things become normal, as what is perverse on page three feels less so on page nine, revealing a dangerous pattern.

My very favorite story is “Old Maid,” so much so that I read it three times through. The cast is a handful of neighbors and the setting does not move beyond their homes, yet what results is a series of surprise revelations and sharp emotions, ultimately of heartbreak; it feels like a full-length novel. A single woman moves into a new house and becomes the de facto baby sitter for the neighboring families. Soon, one family moves away to be replaced by the A—-s (stylized like that and I think perfectly so), who are actually her former love and his new wife. There is a scene in which A invites the neighborhood boys to play basketball, but all of it is told from a faraway perspective, so we decipher what is happening through wordless gestures. The narrator observes, “The boys nodded in that ageless male manner of saying hello,” and it is one of those lines that makes you smile because you know exactly what it means.

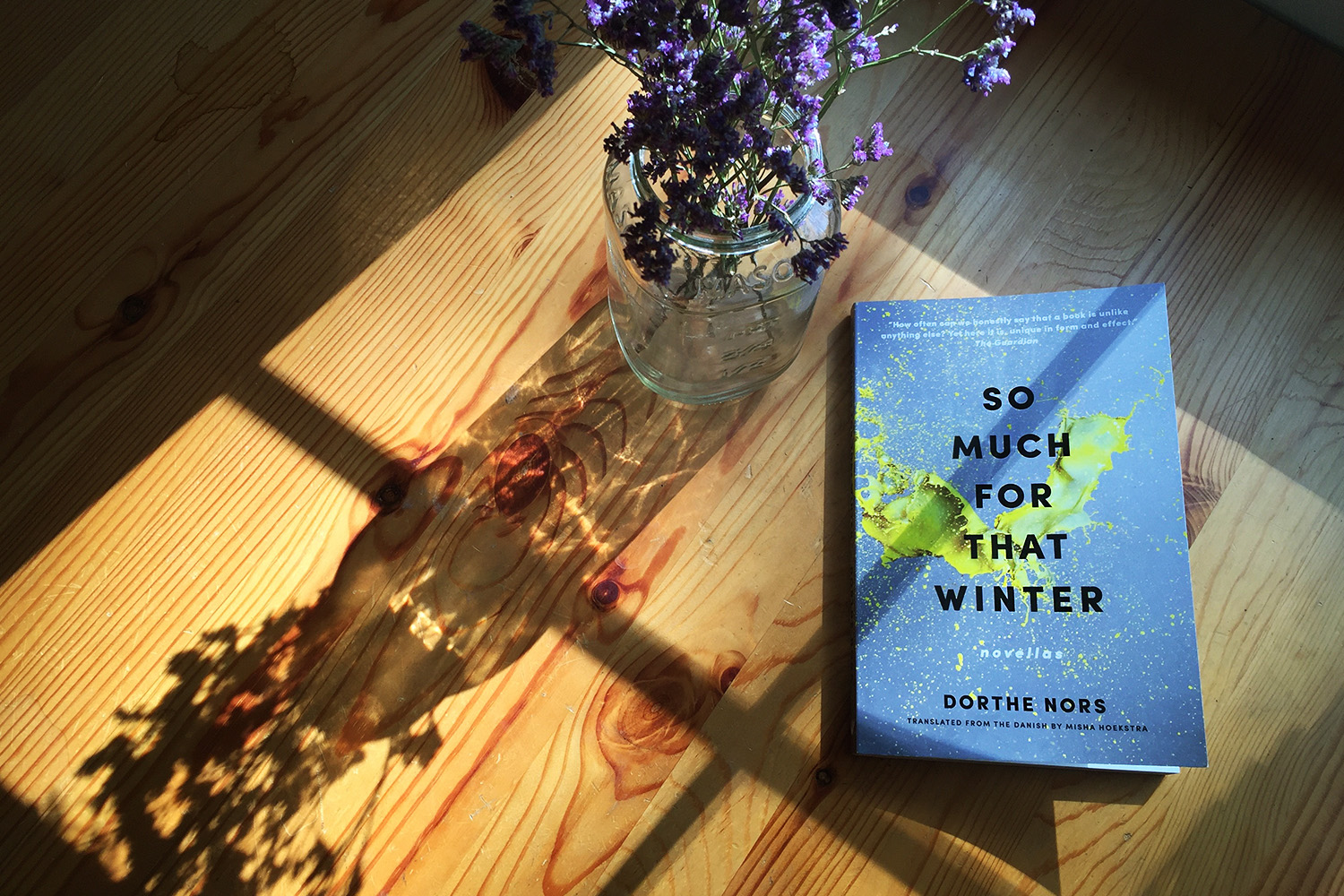

The wonderful thing about a short story is that finishing it never feels like the goodbye of finishing a book. Once I am done with a book, I may never be back, but short stories are easier to revisit, less demanding of our time. Man and Wife has tipped the scales in that I am now officially on a short stories streak, and thanks to it, my expectations are high. Next up: Hot Little Hands by Abigail Ulman.

*

*

“Old Maid” from Man and Wife

By Katie Chase

Published 2016 by A Strange Object

Reflections

Reflections