Having been on a classics streak for quite some time, I knew that I wanted to return to the 21st century for my next read, though I had no idea who, what, or where. I spent the first Saturday of May in Golden Gate Park, and within the first hour I had ventured outside its perimeter on the hunt for coffee. After successful completion, I breezed past and then turned back around into

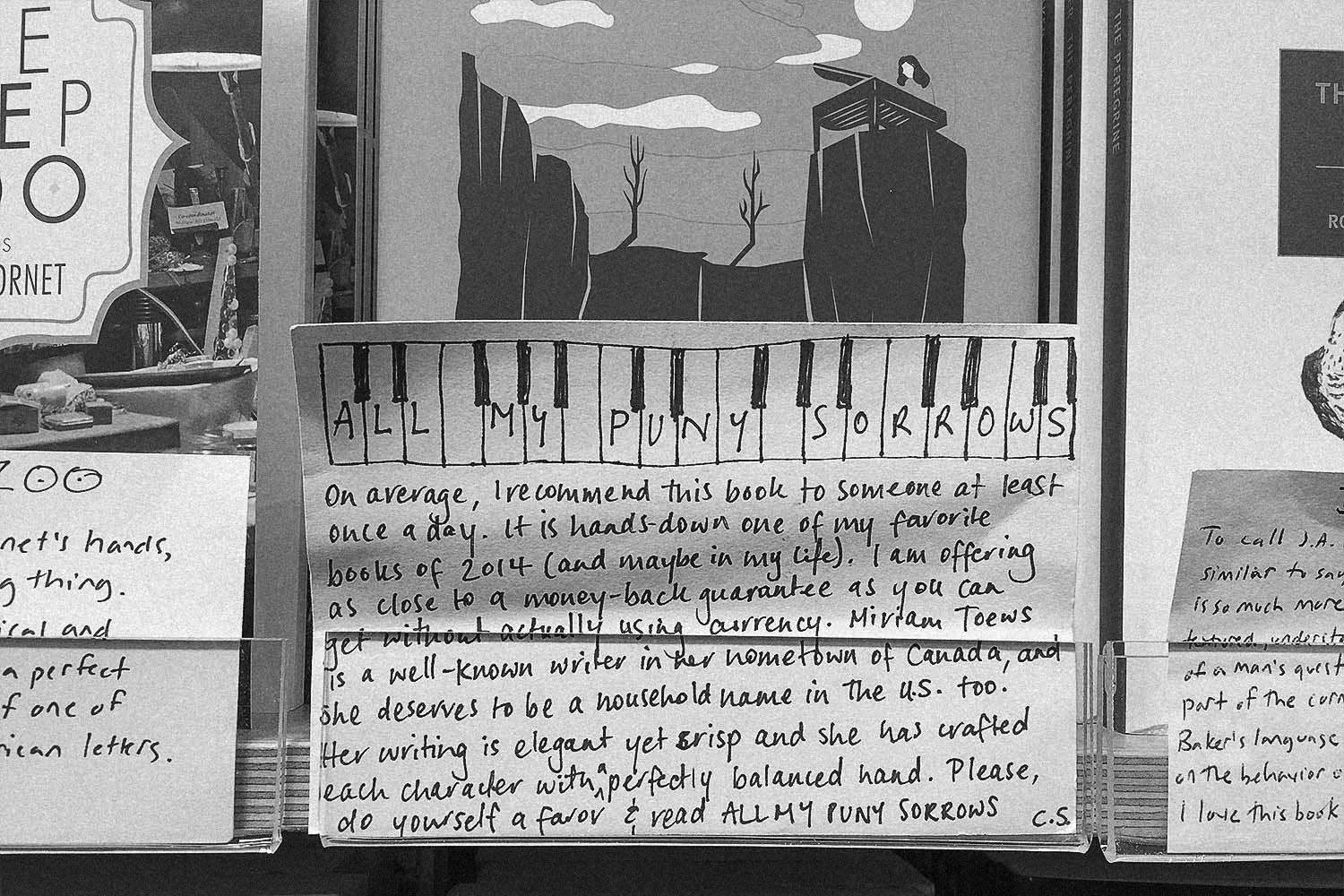

Green Apple Books, encountered the “Staff Picks” shelf, and was startled by this note:

In case you have trouble catching every word, this is the promise: “On average, I recommend this book to someone at least once a day. It is hands-down one of my favorite books of 2014 (and maybe in my life). I am offering as close to a money-back guarantee as you can get without actually using currency…Please, do yourself a favor and read

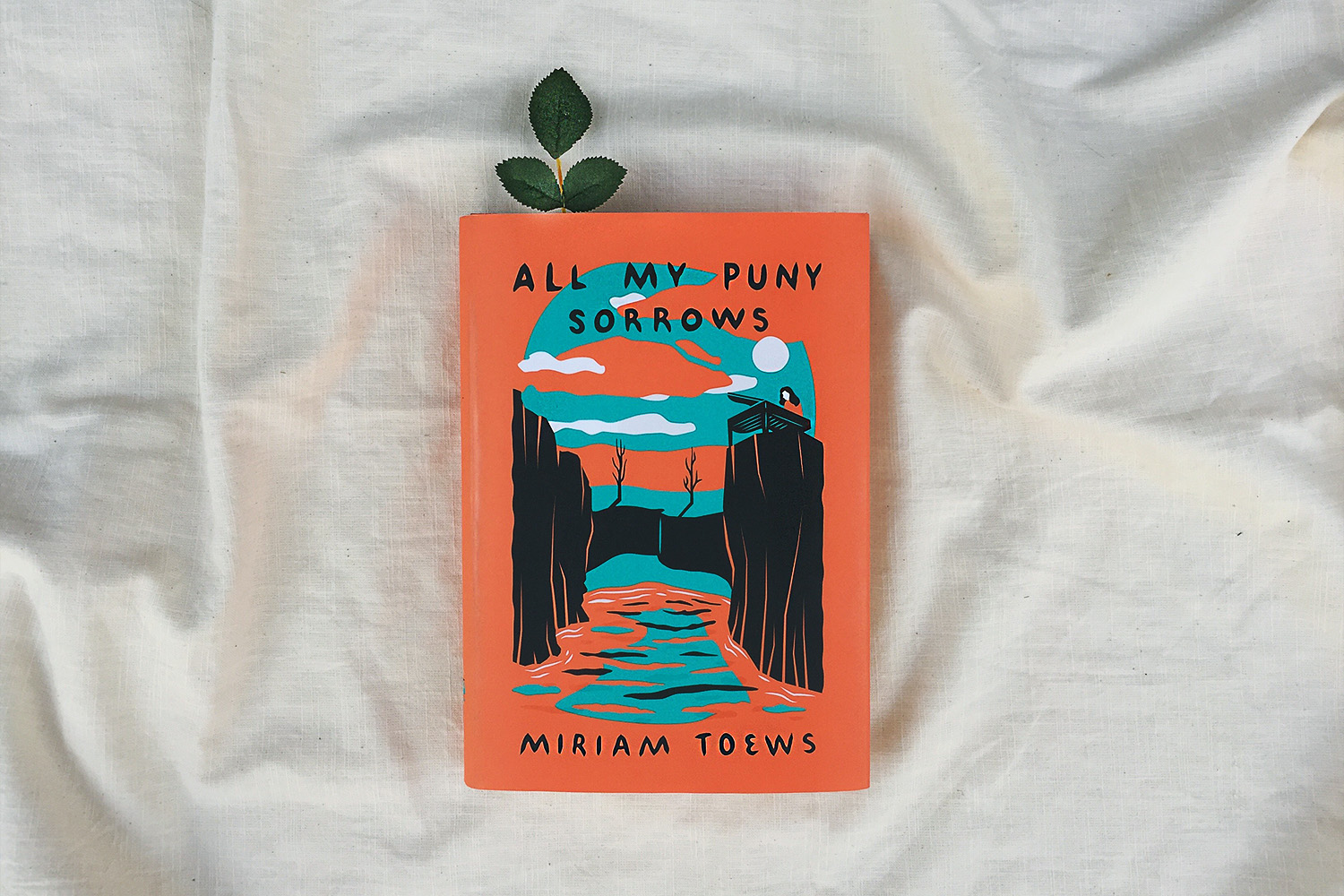

All My Puny Sorrows.”

I do not remember the last time I read such an effusive book review, and I was quickly made vulnerable to its influence, as anything that anyone considers their favorite intrigues me (especially books and songs). I think of it as a shortcut education, or at least enrichment, to expose myself to something that someone else has already studied and determined to be exceptional. You learn a lot about someone by learning their favorites, and if you accumulate enough of that information from enough individuals, you start to learn a lot about people in general.

In Miriam Toews’

All My Puny Sorrows, Elfreida and Yolandi Von Reisen are sisters who mean the world to each other but also suffer the ultimate conflicting interest: Elfreida wants to kill herself and Yolandi wants her to live. I am only 50 pages into the book, but those pages have jumped back and forth between their childhood growing up in a Mennonite household and their adulthood, Elfreida as a world renowned pianist and Yolandi as a divorced mother of two. Elfrida, especially in childhood, is mesmerizing. She is the kind of talented, independent, brilliant, and miserable character that I love.

There is a scene early in the book when the elders of the Mennonite community visit the Von Reisen home to reprimand them for one thing or another. Elfreida goes into the spare bedroom next to the front door and begins to play the piano, which is not allowed in the community. She plays her obsession,

Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in G Minor, Opus 23, a piece she praises for “its total respect for the importance of the chaotic ramblings of an interior monologue” (p. 18). I immediately searched for the piece online and listened to it as I continued to read. I am very eager to dive further into this book, and to discover whether someone else’s favorite will also become mine.

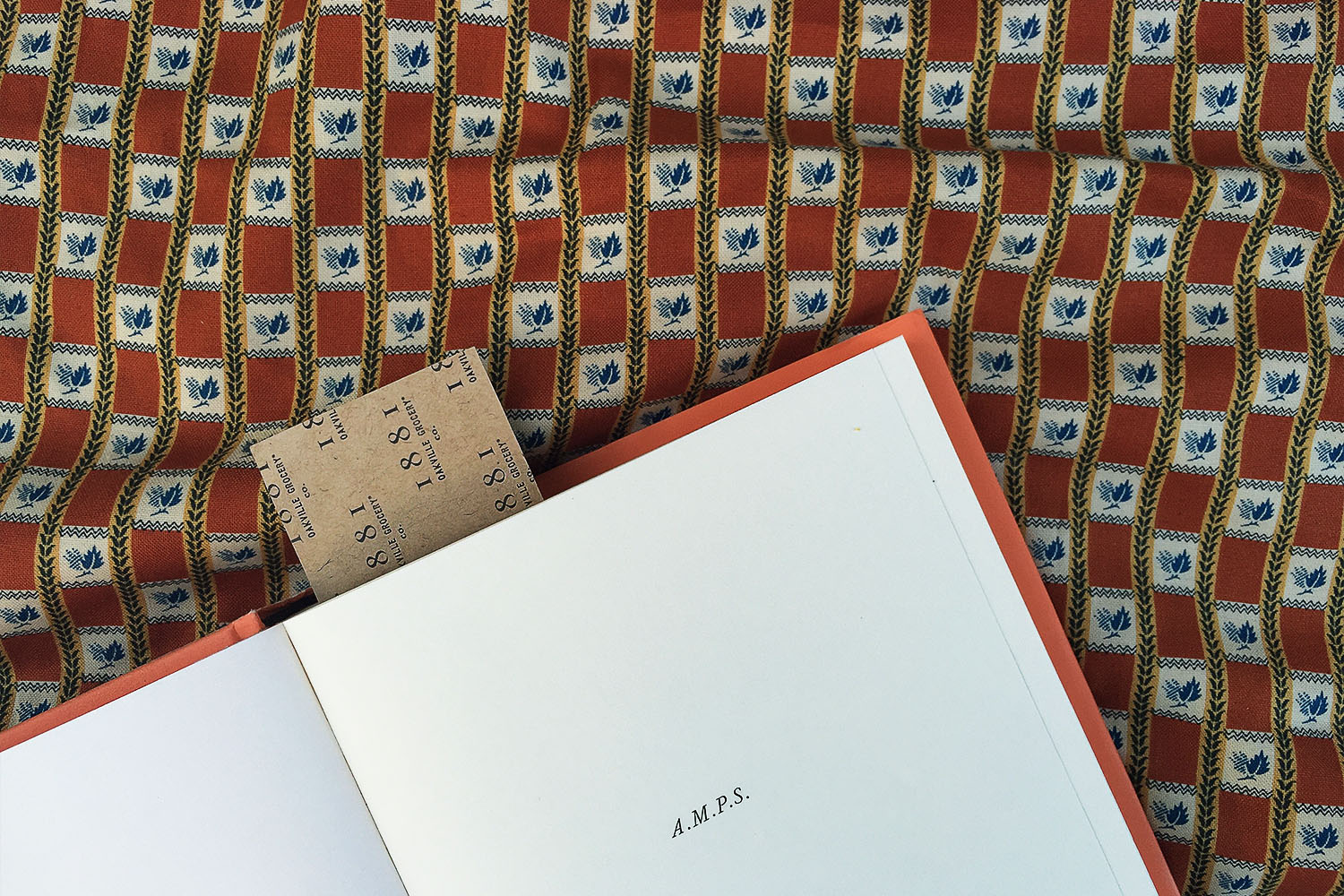

All My Puny Sorrows

All My Puny Sorrows