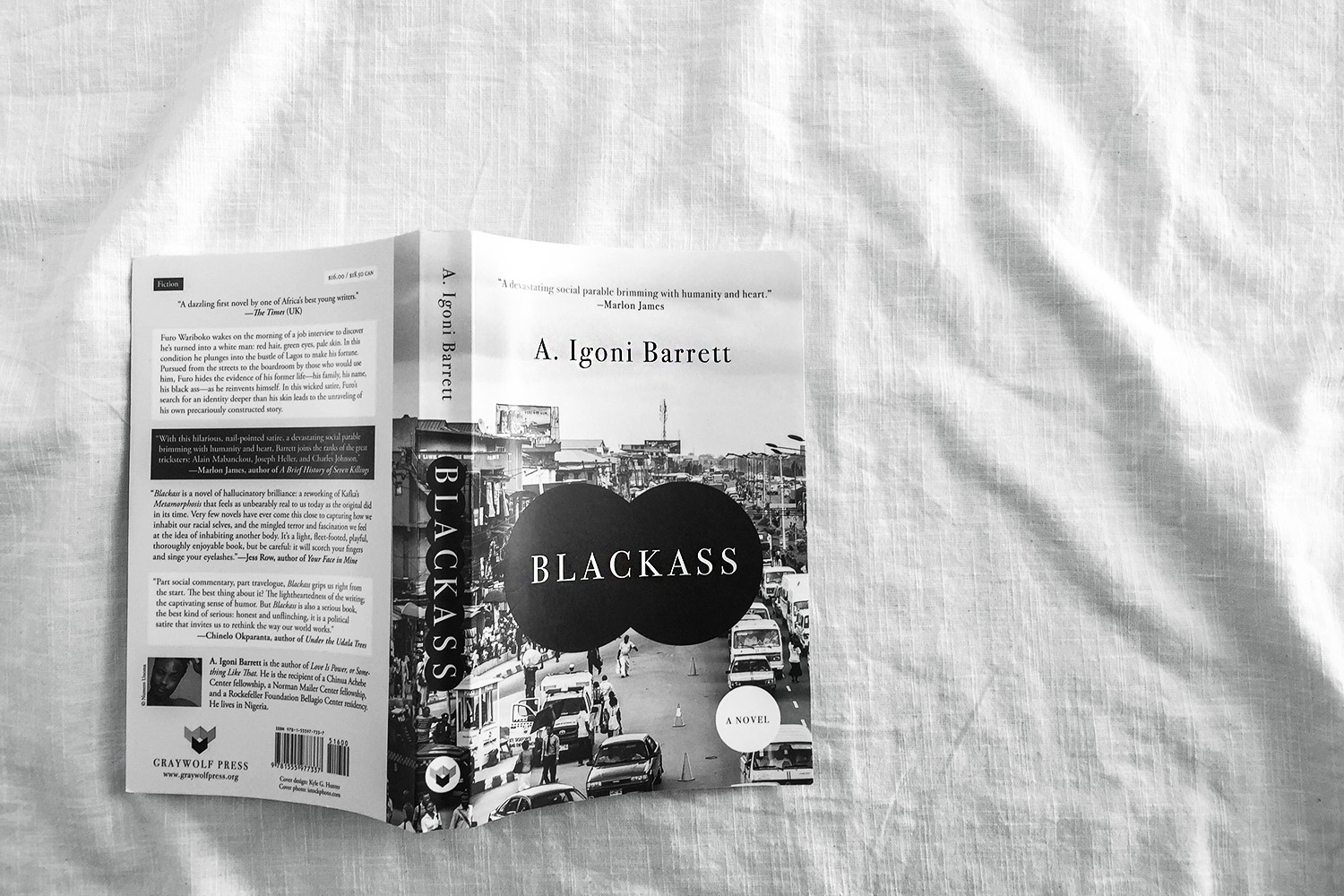

This is a story of a black man who wakes up “alabaster”, of Furo Wariboko who becomes Frank Whyte. On the morning of his Kafka-like metamorphosis, Furo leaves home for a job interview, never to return, choosing instead to forge a new life as a newly minted oyibo. Blackass reflects a world that is far from colorblind, in fact it is a world obsessed with race. All that Furo experiences – job offers, bureaucracy, women, meals, conversations – centers on his newfound whiteness. Of course, a white man named Furo Wariboko wandering Nigeria is sure to inspire an exaggerated response. But rather than a distortion of how we observe race, the book reads more like a parable of its pervasiveness:

“No one asks to be born, to be black or white or any colour in between, and yet the identity a person is born into becomes the hardest to explain to the world” (111).

The book is light, often funny, while addressing issues of race, class, and Nigeria, even social media: “To make money off selling us to ourselves, that’s the business model of social media” (80). The story is free to explore the far reaches of such issues due to its outlandish setup. I am far too unfamiliar with the works of contemporary African authors, but after the reverie of Blackass, I plan to change that.

Best, Yuri

@yuriroho

Post-Reading

Post-Reading