I was warned by a

reader that the book slows down once Catherine arrives at Northanger Abbey, and she was right. While Catherine is in Bath, we get to experience its buzzing social scene starring the entire cast of characters. Three sets of siblings – Catherine and James Morland, Isabella and John Thorpe, and Eleanor and Henry Tilney – find themselves in a web of friendship, flirtation, and ultimately betrayal. It’s actually surprising just how awful a few of these characters turn out to be, namely Isabella. She is so outlandishly self-serving and fake, that she is tolerable only because she provides friendship (admittedly short-lived) to a character we do like, Catherine, and because a villain’s antics are generally entertaining.

Northanger Abbey is not a sweeping or particularly striking story. But it is Jane Austen’s first finished novel and contains bits and pieces that I love. Upon arriving at Northanger Abbey, Catherine sees and hears everything through the lens of a Gothic novel, going as far as to suspect Henry’s father, General Tilney, of murdering or locking up his late wife. No matter how many times her wild imagination is proven wrong, she is relentless, until Henry offers a strongly-worded reprimand and presents what is a clear and beautiful testament of the rational mind: “

Consult your own understanding, your own sense of the probable, your own observation of what is passing around you” (p. 165).

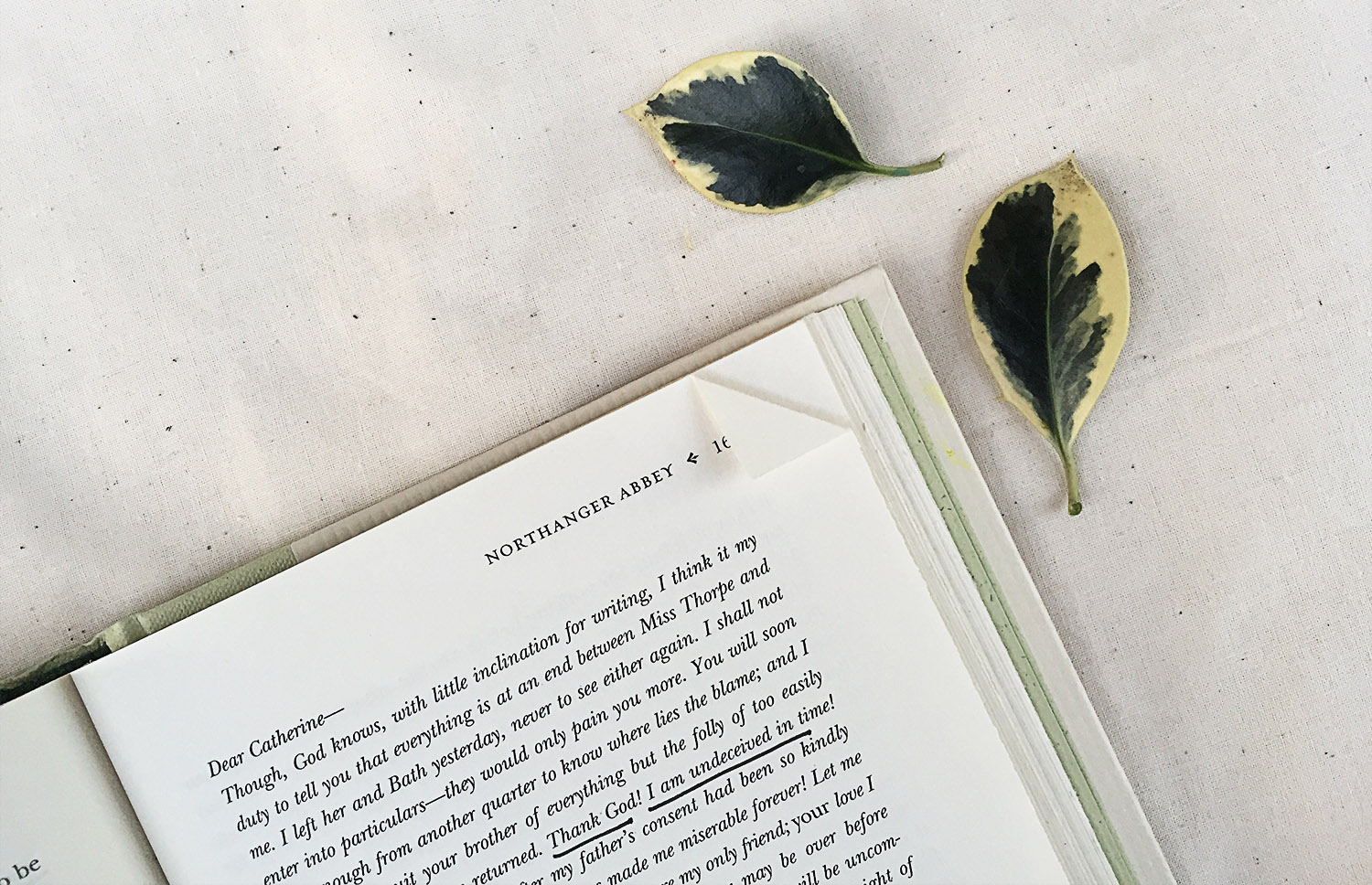

There is also a letter that James writes to Catherine, expressing the end of his engagement with Isabella, who has heartlessly left him in hopes of attaching herself to a wealthier man. He painfully writes, “

Her duplicity hurts me more than all; till the very last, if I reasoned with her, she declared herself as much attached to me as ever, and laughed at my fears.” The final line reads, “

Dearest Catherine, beware how you give your heart” (p. 169). The letter is so heart wrenching that it leads Catherine to cry that she wishes to never to receive a letter again. It is very much worth reading.

Austen ends

Northanger Abbey’s primary love story, that of Catherine and Henry Tilney, on a terribly unromantic yet realistic note. After Catherine and Henry assure each other of their love and commitment, Austen admits that Henry’s knowledge of Catherine’s infatuation with him had been originally “

the only cause of giving her a serious thought” (p. 206). Indeed, how many relationships are forged simply by the flattery and pleasure one receives from another’s obvious affection? Jane Austen gets it.

Classic

Classic