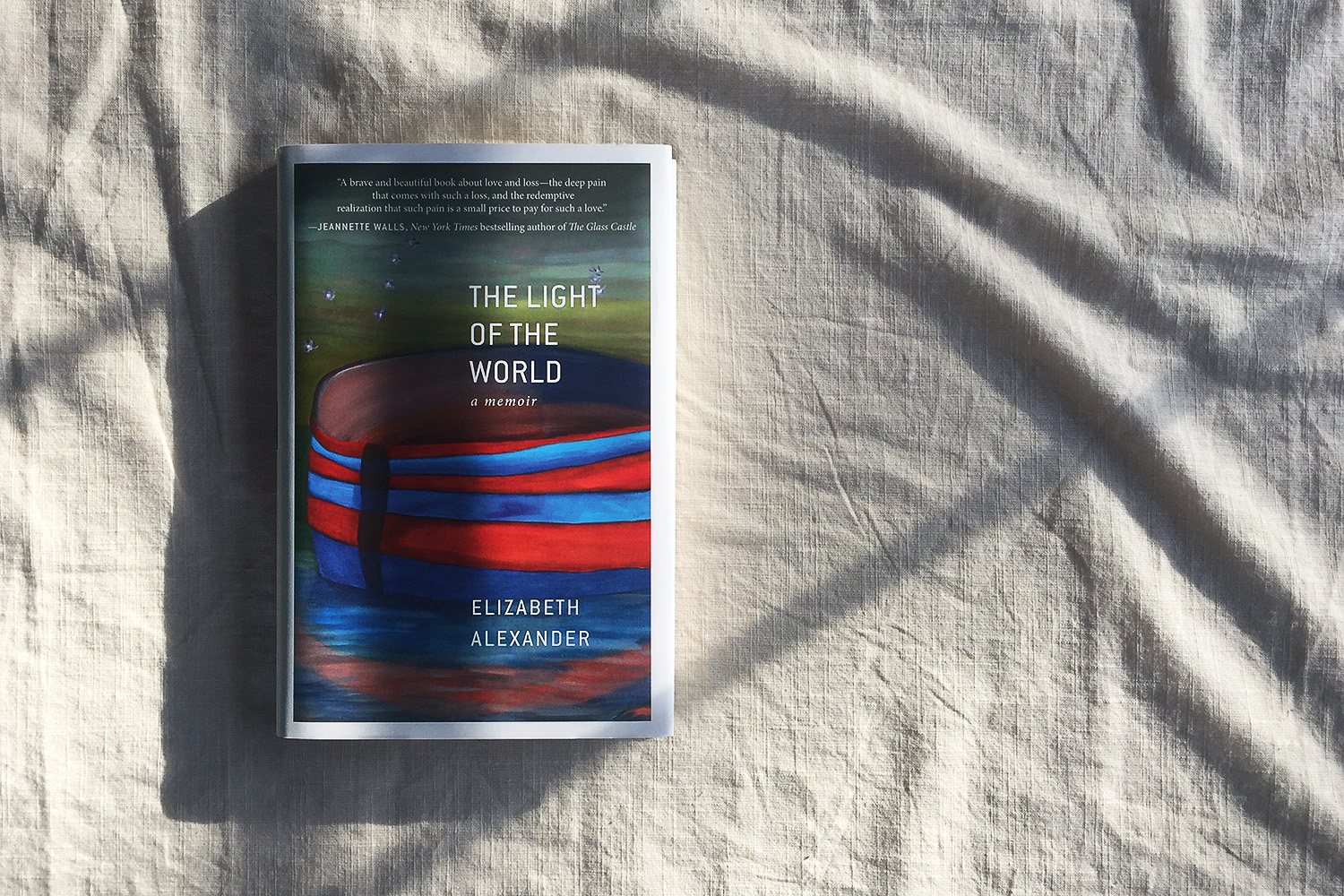

“The story seems to begin with catastrophe but in fact began earlier and is not a tragedy but rather a love story. Perhaps tragedies are only tragedies in the presence of love, which confers meaning to loss. Loss is not felt in the absence of love.”

The Light of the World is a moving portrait of the author’s husband——an impressive man named Ficre Ghebreyesus——their love story, and how she copes with his sudden death. She discusses Africa, art, flowers, and food (there are recipes); she annotates poems on death; she recalls dreams; she introduces an endless stream of family and friends; she shares the most intimate details of marriage (“We shared days I can only call divine,” she writes).

As I neared the book’s end, I prolonged the inevitable by flipping back through the pages, revisiting scenes and scanning for marks I made. “Memories are what you no longer want to remember,” Joan Didion writes in Blue Nights, her own memoir of loss. But perhaps in their very ability to awaken the past, memories alone are redemptive. Within his wife’s prose, there is still Ficre, his presence strong.

Reflections on death, especially ones written so beautifully, can be tricky to process. As a reader it can be tempting to romanticize heartache, to become lost in its reverie. But there is no such luxury in The Light of the World. Love and loss sit side-by-side only to emphasize each other, to draw out each other’s extremes. “Ficre everywhere, Ficre nowhere,” she writes, and the magnitude of that is felt on every page.

*

Quote

*

The Light of the World

By Elizabeth Alexander

Published 2015 by Grand Central Publishing

Reflections

Reflections